Parliaments and Other Corporations

“Nele JCP said that every act of Parliament ought to be presumed (entendus) general, and ought to be known (conus) to everyone within the realm, because it is made for all the realm, because everyone has his attorney (representative) in Parliament, that is, the knights ‘of the shire’ (in English) for the country (pais), and the burgesses for the cities and boroughs.” (Mich. (2nd) 21 Edw. 4 28 fol. 55b-59b)

Here we see a fairly old case concerning the nature of Parliament. What is Parliament? Well, it is a corporation. This is more clearly explained in William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the law of England:

“THE conftituent parts of a parliament are the next objects of our enquiry. And thefe are, the king’s majefty, fitting there in his royal political capacity, and the three eftates of the realm ; the lords fpiritual, the lords temporal, (who fit, together with the king, in one houfe) and the commons, who fit by themfelves in another. And the king and thefe three eftates, together, form the great corporation or body politic of the kingdom.” (1 Bl. Comm. 149)

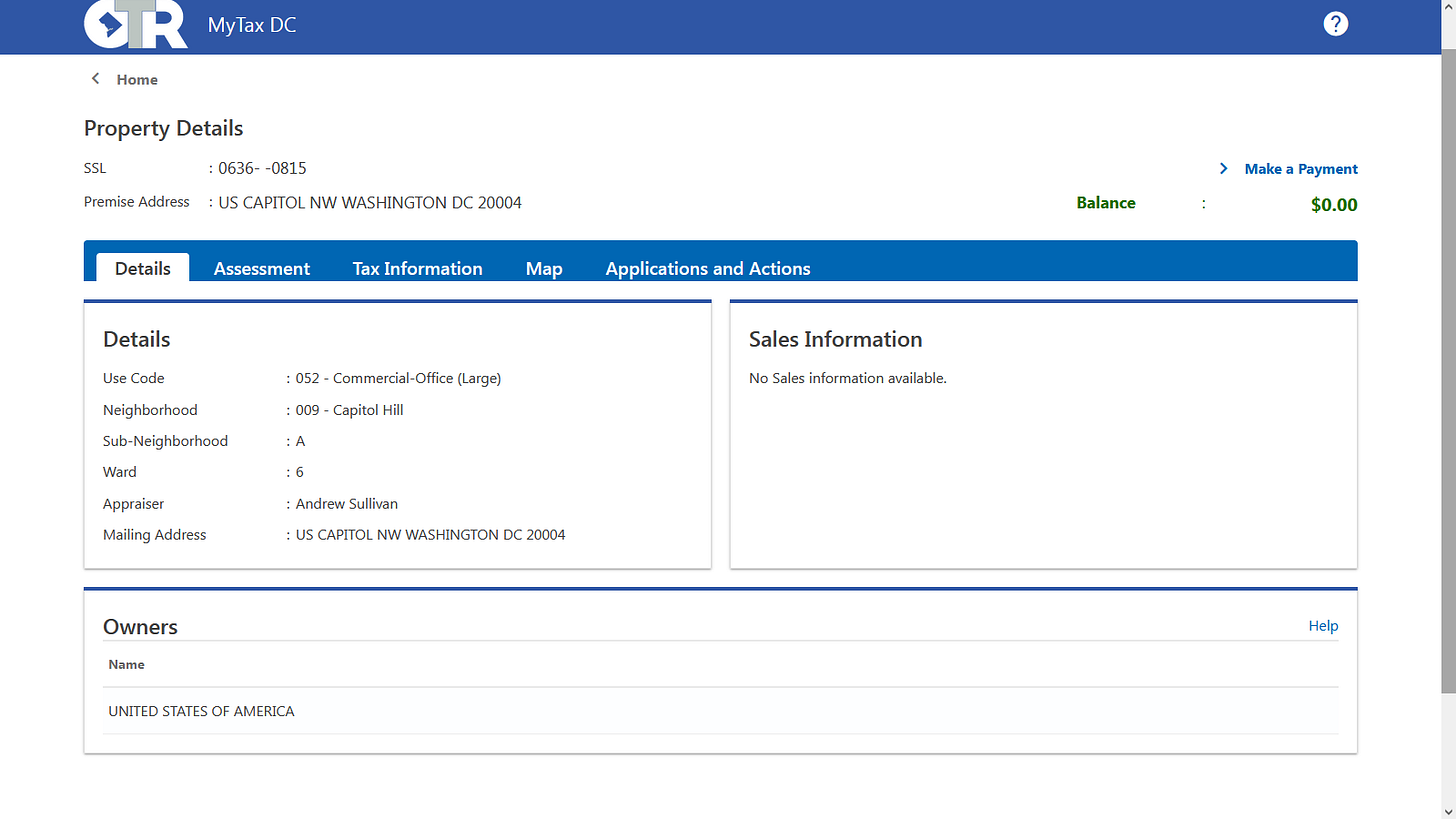

And this is true for any sort of deliberative assembly: it is a corporation. This much is true of THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Consider the Land Title for the Capitol Building and Grounds in Washington, DC:

The “owner” of the “property” is listed as “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.” That is not a natural person, and, therefore, it must be a political person, or corporation. One way to think about this is that corporations do not exist in nature, and so, considered naturally, all lands held by corporations are actually terra nullius, or no man’s land, and they may be occupied by anyone, according to the law of nations. Those who do in fact occupy them may be said to have a transitory property, by occupation, but this natural property is determined as soon as one moves off of the spot of ground one occupies; it does not extend to an entire building, because, in nature, there are no buildings. Cicero defines it this way:

A doctrine well illuftrated by Cicero, who compares the world to a great theatre, which is common to the public, and yet the place which any man has taken is for the time his own*

*Quemadmoaum theatrum, cum commune fit, recte tamen dici poteft, ejus effe eum locum quem quifque occuparit. Ce Fin. L. 3. c. 20. (2. Bl. Comm. 4)

Whether this digression proves true or not, we are left, again, with the question of “who can form these corporations?” We are also left with the question of how one is made member of them. The quote at the beginning, from Nele, JCP, is from a time when involuntary servitude existed: a Lord could bind his serfs to covenants, and one could be involuntarily represented and bound by the servitudes contracted by one’s representative. With the abolition of involuntary servitude, or with the revelation of freedom as our natural power, what is to be said of these legacy corporations that seek to steer us against our will, to impose servitudes upon us as a condition of life?

Also, where is it that people learn about these things? In the next article, I will consider perhaps one of the most important and arcane matters: the existence of a species of corporation called Universities.